Dear Mr. Salinger,

It has been thirty years since your last published word, and nearly just as long of people wondering why.

Maybe you already told us.

In The Catcher in the Rye, published twenty years before you closed the door, Holden Caulfield says, “I swear to God, if I were a piano player or an actor or something and all those dopes thought I was terrific, I’d hate it. I wouldn’t even want them to clap for me. People always clap for the wrong things. If I were a piano player I’d play it in the goddam closet… those dopes that clap their heads off—they’d foul up anybody, if you gave them a chance.”

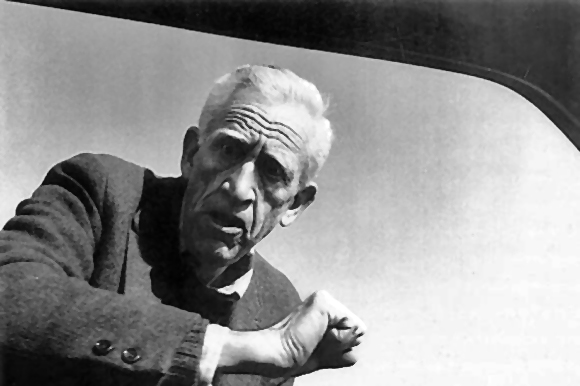

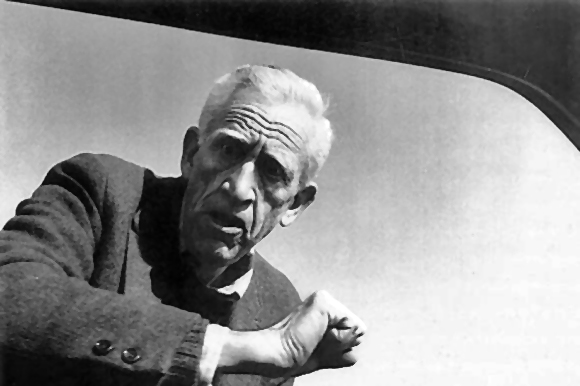

And then there are Seymour’s last words before he shoots himself: “I have two normal feet and I can’t see the slightest God-damned reason why anybody should stare at them” he says of a befuddled stranger in the elevator who had no interest whatsoever in his feet. It is a cruel paradox that the sensitivity that begets beautiful art often makes life unbearable for the artist. We can at least be grateful you have chosen a gentler escape than Seymour or Van Gogh.

I am not brave enough to offer any specific applause for your writing, but I do want to thank you. I remember reading a book of yours on the train to work, having to stifle the urge to miss my stop and spend the day just reading and riding, having to force myself to close the book and get off. I went about my day, but for a long time after I stopped feeling the train’s momentum, I could still feel yours. I believe I still do, softly, and I believe I am better for it.

That’s all. I do not consider your work sacred, or you a guru. Truthfully, I do not think of you much at all. I want nothing from you but more, and if I could get that without involving you, I would, believe me.

I expect this sort of appeal disturbs you. For Raise High the Roof Beams, Carpenters and Seymour, an Introduction you wrote the following dedication: “If there is an amateur reader still left in the world or anybody who just reads and runs, I ask him or her, with untellable affection and gratitude, to split the dedication of this book four ways with my wife and children.”

I am not sure what you mean by amateur reader, but I know I do not read and run. When I find authors I like, I get greedy. I devour their work, and I look for more. Sometimes I find that I ought to have moved on sooner – they decline or I outgrow them. I may reach that conclusion with your work, but I’d still like to find out. I’m telling you I love good writing as much as anything life offers. I do not read and run.

And neither do you.

In fact, in the very book that offers the above dedication you include a long quote by Franz Kafka, and then explain, by way of Buddy Glass, how Kafka is one (and Van Gogh another) of a handful you run to for their wisdom on art.

For the dust jacket of this book you wrote “I have several new Glass stories coming along…” and in the decades since, you have reluctantly confirmed more than once that you continue to write. Your readers, for a long time now, have had cause to hope for more. But it occurs to me that Kafka, whom you esteem so highly, intended that his unpublished work be destroyed, never read, and I worry you intend the same.

At the risk of being indelicate, I have been prepared to wait out your life for the balance of your work. Born long after you, I figure I can afford to be patient. If applause disturbs you, then keeping your audience at a distance seems reasonable, and not at all arrogant or deranged. But destroying your work, I find unreasonable, and unkind. If you disagree, please consider how grateful you are that Max Brod betrayed Kafka by publishing his work instead of burning it.

Won’t you do the world the same favor, Mr. Salinger? You cannot be the only human with any sense or decency. We cannot all be clapping at only the wrong parts. On behalf of the few who get it right—though I may not be among them—please, leave us the rest.

With hopeful gratitude,

Daniel Kaufman

P.S. Nobody is looking at your feet.

April, 1995